By Amanda Blank

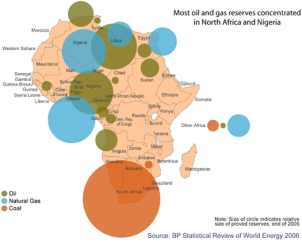

Africa is a significant exporter of cheap energy, namely dirty fuels like gas, oil, coal, and uranium for nuclear energy. While energy is cheaply exported, the local consequences are very damaging, and communities do not reap benefits from the utilization of their natural resources. Though there is no shortage of energy production or resources in Africa, there is a constant push for exploitation, most recently natural gas off the east coast.

Approximately 30 African countries face endemic power shortages and 589 million people in sub-Saharan Africa—68 percent of the population—do not have access to electricity or other modern energy services. Lack of electricity throughout Africa is particularly detrimental to society advancement in 5 ways: poor healthcare, stifled economic growth, limited or no education, safety concerns, and toxic fumes from indoor open fires. There is international consensus that lack of power in Africa is an issue that needs remediation and immediate attention. However, providing increased access to energy will not solve any long-term issues if it is sourced from dirty energy projects. Repercussions of proposed energy projects funded by special interest groups could consequentially propel Africans into much deeper trouble.

In June 2013, President Obama announced a new $7 billion U.S. commitment to the energy sector in Ethiopia, Ghana, Kenya, Liberia, Nigeria, and Tanzania. The President’s Power Africa initiative is aimed at increasing electricity generation by 10,000 megawatts for 20 million households and businesses over the next 5 years. His plan includes investments from the Export-Import Bank, the Overseas Private Investment Corporation, the Millennium Challenge Corporation, USTDA and USAID. Power Africa also includes $9 billion in commitments from the private sector, including General Electric, Heirs Holdings, Symbion Power, Aldwych International, Harith General Partners, and Husk Power Systems.

In correspondence, U.S. Representatives Ed Royce (R-CA) and Eliot Engel (D-NY) introduced the Electrify Africa Act in the House. The bill seeks to prioritize and coordinate U.S. government resources to achieve three goals in sub-Saharan Africa by 2020: (1) Encourage the installation of at least an additional 20,000 megawatts of electrical power; (2) promote first-time access to electricity for at least 50 million people, particularly the poor; and (3) promote efficient institutional platforms that provide electrical service to rural and underserved areas.

Whereas Power Africa and the Electrify Africa Act include language about developing “an appropriate mix of power solutions, including renewable energy,” clean energy makes up less than 0.3 percent of the White House initiative’s budget. Natural gas, on the other hand, is front and center. Proponents of these initiatives have expressed strong enthusiasm over the discovery of significant shale gas reserves off the coasts of Tanzania and Mozambique and large production areas in Nigeria. With the region possessing four percent of the world’s verified reserves of natural gas and 10 percent of the world’s unexploited potential for hydropower, these resources are seen as opportunities to create an energy system that revolves around them. Power Africa states utilization of natural gas and hydropower as sustainable resources that will contribute to climate change mitigation strategies. In actuality, this is largely erroneous. Hydropower dams have a long history of causing environmental justice conflicts all over the world, and construction and ecosystems impacts certainly remove them from the “clean” energy category. Though natural gas is often portrayed as a cleaner fossil fuel, it can be even more polluting than dirty coal. Methane is released during its production, which a greenhouse gas 20 times as powerful as carbon dioxide. Furthermore, extraction of gas from the expansive reserves off the coast of Africa could be a dangerous tipping point, particularly for climate change implications in Africa.

The International Panel on Climate Change and World Bank have warned that Africa will likely experience some of the developing world’s most severe effects of climate change, compromising agriculture, human health, coastal habitation, and economy. Due to drought, agriculture yields could drop by 50 percent in some countries by 2020, and crop revenues could fall by as much as 90 percent by 2100. Food insecurity and exacerbated malnutrition in turn will compromise already poverty-stricken areas. Sea level rise is anticipated to threaten the 320 coastal cities and 56 million people living in low-lying coastal zones around the continent. The cost to African nations of adapting to a warmer world could amount to between 5 and 10 percent of their gross domestic product.

While strategic rhetoric around the two initiatives is about improving quality of life by increasing energy accessibility for rural Africans, the approaches being outlined will lead to large, climate-polluting, centralized power projects, instead of decentralized, renewable energy systems that are clean and locally empowering. Centralized energy is an inefficient method of providing Africans with energy; money and electricity will be wasted by constructing transmission lines that reach distant rural villages. Rather, facilitating local generation and direct access that places control in hands of community members would be more efficient, environmentally and socially. The International Energy Agency notes that investment needs to go to small-scale mini-grid and off-grid solutions—which are more efficient at delivering electricity to people in rural areas, where 84 percent of those lacking power live—not to centralized power plants. Small-scale systems produce energy at the household and community level from renewable sources, including micro-hydro, solar, wind, and biogas. With U.S.-funded, centralized energy, Africans miss out on the opportunity to develop their grid in a self-sufficient, sustainable manner. Both initiatives place increasing investment by U.S. energy companies in Africa at their center, which should raise skepticism, along with alarm.

As national U.S. policies are already useless enough in combatting climate change, these new initiatives in Africa directly contradict the energy targets of the 5th UN session of the Open Working Group on Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs):

- Target 1. Provide energy access to people relying on none, low or bad quality modern energy. Especial attention must be given to poor economies access to clean energy and its link to the reduction on health causalities due to indoor pollution. Equally important is to stimulate the ownership of renewable energy production micro units at local level.

- Target 2. Double the renewable energy share in the global mix.

- Target 3. Double global energy efficiency in production, distribution and consumption.

- Target 4. Develop strong political and governance frameworks, at global, regional and national levels to support the establishment of new energy systems.

Not only are Power Africa and the Electrify Africa Act supporting different energy targets than SDGs, they are likewise in opposition to the “Sustainable Energy for All” (SE4ALL) initiative launched by UN Secretary General Ban Ki-moon, which with the U.S. has involvement. This means that these African initiatives are contradicting international goals and prior U.S. support given to SE4ALL. The lack of cohesion between policies is quite astounding. To pour salt in Africa’s already deep wounds—all of the countries involved in Power Africa—Ethiopia, Ghana, Kenya, Liberia, Nigeria, and Tanzania—have also made commitments with SE4ALL to develop sustainable energy systems. This feels manipulative and deceiving because the U.S. initiatives are not clean or sustainable but have been presented under those brands.

Though the U.S. taking initiatives to provide wider access to energy and improve quality of life for Africans is a noble cause, the methodology is flawed. They are supporting increased fossil fuel consumption and extraction, inefficient means of distributing electricity, and an energy structure dominated by political and corporate interests. By fostering centralized, fossil fuel development that will financially benefit U.S. corporations and government power, rather than local African communities, deeper issues will be constructed. Exacerbating climate change implications in Africa and skewed power structures are long-term effects of the U.S. initiatives and should be internationally, publically challenged before the damage is complete.

Picture from: http://blog.foreignpolicy.com/node/system/files?file=images/africa_energy_0.png

Excellent article! It is indeed a fact that an efficient use of rhetoric can make something seem what it is not. The program names all sound positive, but when a person (Amanda) looks deeper, the truth is totally different. It is sad that absolutely everything ultimately ends up being about money and a self-serving motive. Africa gets the short end of the stick every time. Tragic!